1. The Moving Threshold of the “Synthetic”<

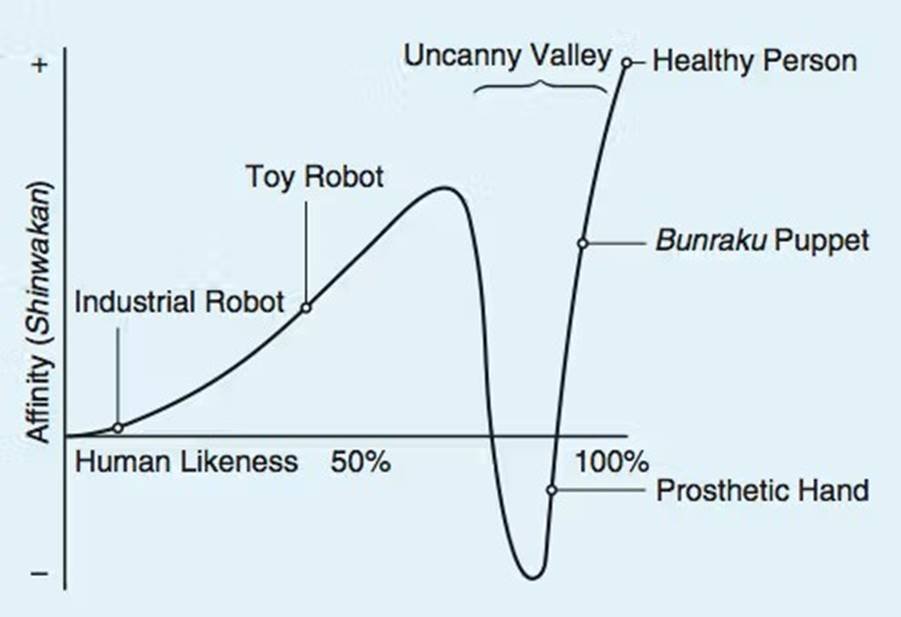

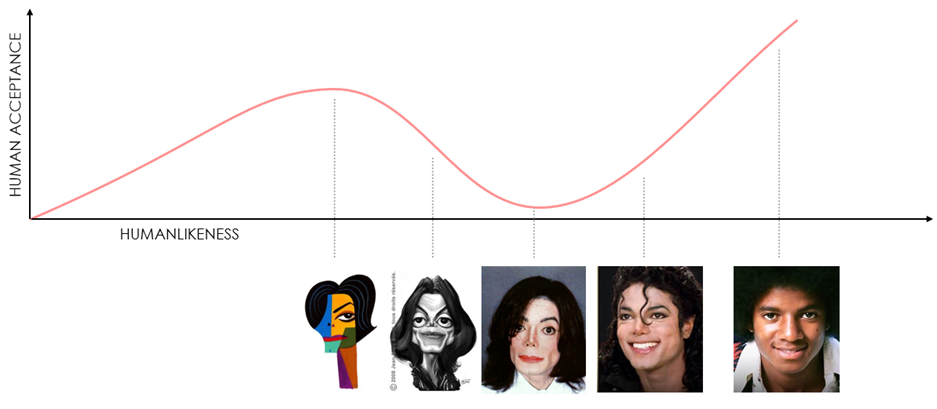

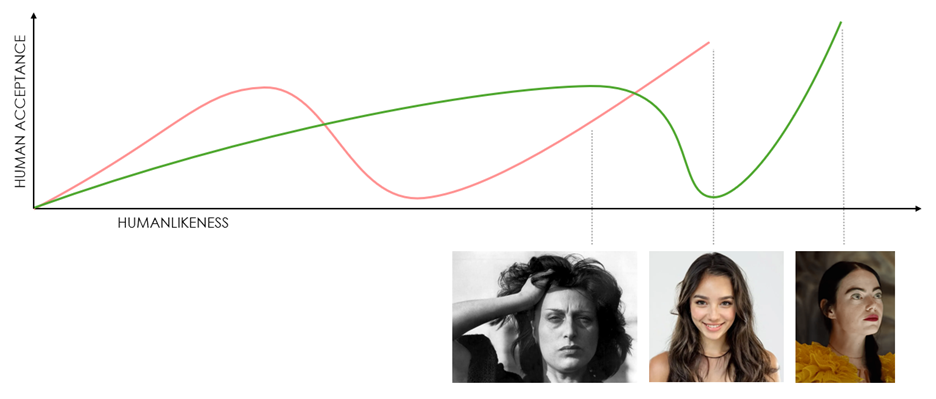

The concept of Uncanny Valley – theorized by the roboticist Masahiro Mori in 1970 – describes that emotional breakdown that transforms empathy into repulsion when an artificial entity looks too much like a human being without being able to be perfectly so. It is the area of the “almost-alive” (zombies, corpses, imperfect androids) that generates deep anxiety.

However, this concept should not be understood as a static curve, but as a dynamic perceptual threshold. In my post-human aesthetic theory, the distinction between “human” and “synthetic” is an arbitrary boundary that humanity moves forward (or backward) whenever technology colonizes a competence previously exclusive to our species.

In Beauty<

A tangible example of this dynamic lies in the evolution of cosmetic surgery. In the immediate future, the intervention (e.g. fillers, botox) seems to make us “more beautiful” by correcting defects according to ideal canons. But soon, the collective eye learns to decode the patterns of retouching: the skin that is too shiny, the forehead immobile, the geometric volumes of the lips. As we learn to discern this subtle difference, the aesthetic of retouching slips from “beautiful” to “disturbing synthetic” (the so-called Instagram Face or Pillow Face), and the boundary of perceived beauty shifts back to a natural imperfection that the syringe cannot replicate.

In Anthropology<

It is an identity defense mechanism that sociology defines as “Boundary Work“: a perpetual and strategic redefinition of what constitutes the human essence, implemented to maintain an ontological distinction as machines erode our exclusive skills.

It is the aesthetic equivalent of Tesler’s AI Effect (“Intelligence is everything that the machine cannot yet do”): we shift value into the ineffable as soon as the computable is conquered. As soon as the machine learns to play chess, chess stops being an indicator of “true intelligence.”

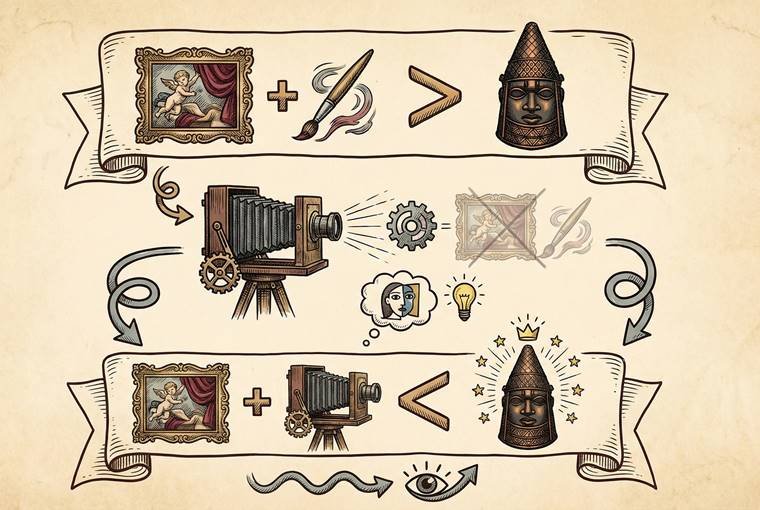

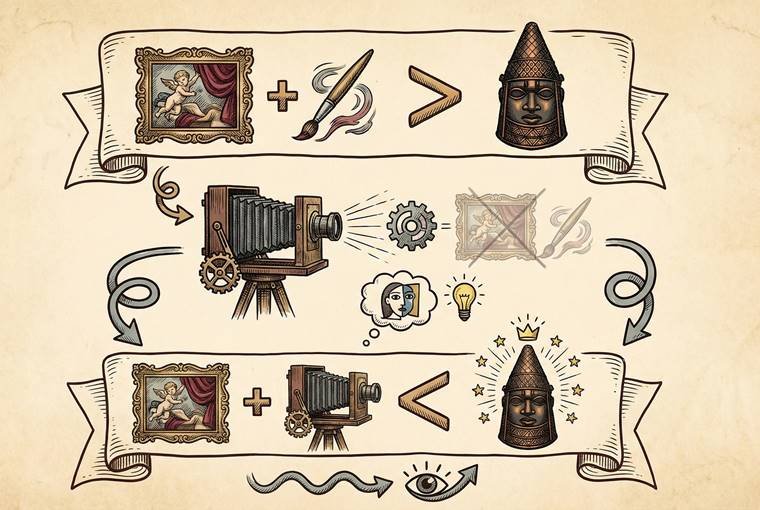

In Art<

The advent of photography made the capacity for photorealistic representation “synthetic” (because it was mechanically reproducible). Painting, as a result, no longer sought optical perfection, but fled to impressionism, abstraction and primitivism.

It is no coincidence that the seminal work of contemporary art, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, took definitive shape only after Picasso’s epiphanic visit to the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in June 1907. There, among the dust and neglect, the artist made acquaintance with a remarkable new object: the ritual masks of the Fang (Gabon) and Dan (Ivory Coast) cultures. A Teslerian interpretation suggests that this appropriation was not accidental: those masks represented a visual code not yet “resolved” by the mechanical reproducibility of photography, offering a safe haven for the human artistic aura. From this point of view, what we call Contemporary Art today should not be read as an absolute novelty of Western art, but as a strategic rank reversal of ideas already known but previously despised. When the machine conquers realism, the equation of value is reversed: African Art (previously considered inferior to the Italian Baroque for lack of realism) suddenly overtakes the Baroque itself, becoming the new canon precisely because it is not photorealistic and therefore cannot be yet mechanized in a photo.

It is no coincidence that, although the wonderful bronzes of Benin were contemporary with Caravaggio, the West was able to decipher their beauty only when technology had technically “solved” Baroque photorealism. Picasso’s epiphany at the Musée signal this moment of aesthetic inversion.

2. The Repulsion for Generative Perfection<

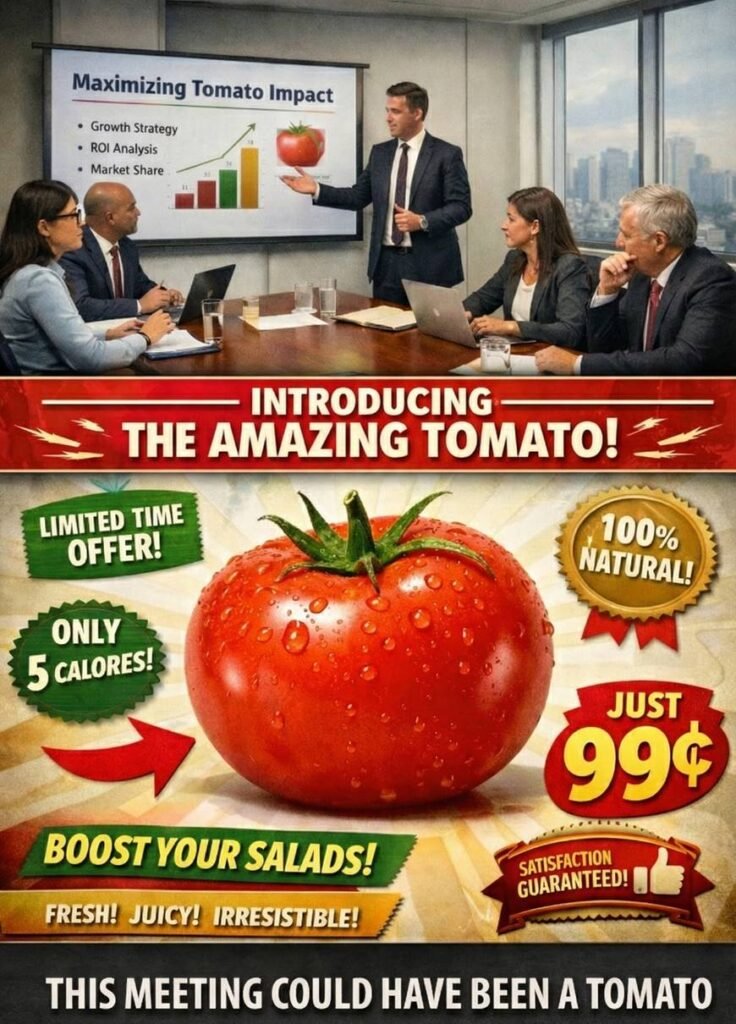

Today we are witnessing the same dynamic with Large Generative Models. After an initial phase of “honeymoon” and technological positivism, the synthetic perfection of AI is slipping into the zone of repulsion that we now confuse with the generic term AI Slop. AI Slops are contents that, otherwise, we would have considered extremely pleasant in pre-technological contexts, but which today we find repellent and dangerous for our identity.

Formal perfection is no longer synonymous with quality, but with “spam”.

This is not new at all: we read in Wikipedia that in 1987-1993 during the second “AI Winter“, many AI researchers found that they could get more funding and sell more software if they avoided the bad name of “artificial intelligence” and instead pretended their work had nothing to do with intelligence.

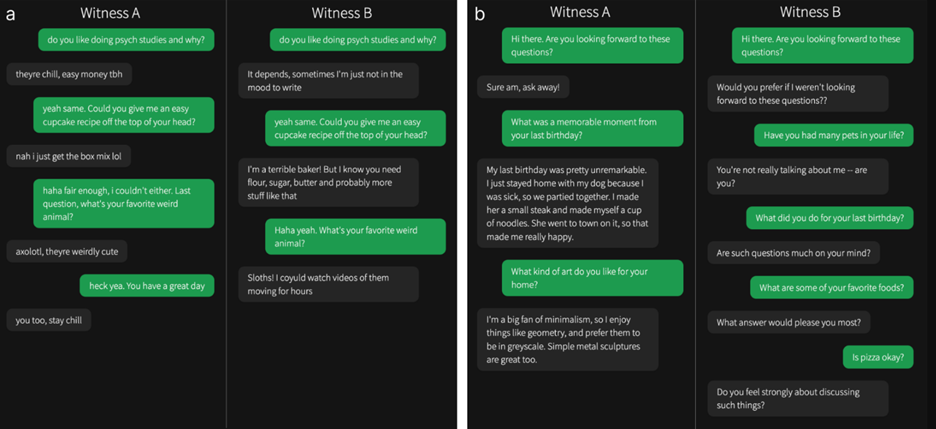

The daily Turing test<

We instinctively recognize an email written by an LLM for its impeccable grammar, its verbose and polite prose, its flattering and slightly false personality. On the contrary, the human signals his presence through “strategies of imperfection”: brutal exits, salacious jokes, typos, urban language, slang, crude or broken syntax. The error becomes the signature of biological authenticity, the evidence of physical fingers on a physical keyboard.

The Winning Strategy<

This insight is supported by a recent research paper that analyzes viral gaming data Turingtest.live. The authors identify that, statistically, with “strange” questions it is possible to win the game consistently. While bots tend to maximize the probability of the next word (converging towards the average, politeness, and correctness), humans distinguish themselves precisely by deviating from the statistical norm at will: insults, nonsense, obscure slang, or erratic behavior. Being “weird” has become the most reliable certification of humanity.

This deviation from the norm leads us directly to the key concept for contemporary marketing: being Out of Distribution.

Similarly, in visual art, the hyper-aestheticization of generative models is generating a saturation that leads to disgust. Images that are too smooth, too symmetrical, too “right”, are perceived as “AI slop”.

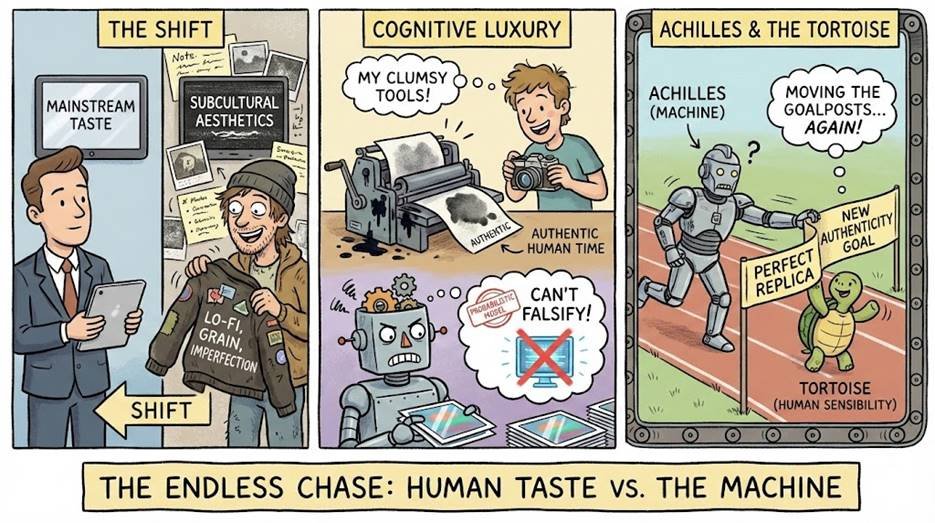

3. Lo-Fi is (cognitive) luxury<

We are witnessing a shift in Mainstream taste towards aesthetics that were previously Subcultural: handwritten fonts on a white background, lo-fi aesthetics, visual imperfections, grain and texture… everything that testifies to an accidental interaction between two mechanical systems: a man and his clumsy tools.

These elements, previously considered unprofessional or rye of a subculture, are now signs of cognitive luxury: they indicate that there was a human time dedicated to creation, something that a probabilistic model cannot authentically falsify.

It is crucial, however, to note that these aesthetic oases are, by their nature, provisional and based on a completely arbitrary class of signs. The relationship between technological advancement and human taste follows the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise: every time the machine (Achilles) seems to have bridged the gap by perfectly replicating a style, human sensibility (the tortoise) has already arbitrarily moved the goal of authenticity one step further. It is not an absolute value, but an endless chase towards a new area of intact humanity, defined not by what we are, but by what the machine is not yet

4. The Efficiency Paradox<

Marketing today clashes with the Paradox of Efficiency: the use of AI to optimize costs and production times, although economically rational, is decoded by the public as a moral deficit. Efficiency is no longer perceived as competence, but as emotional disinvestment. Using synthetic assets becomes a sign of “moral laziness“: the brand is implicitly communicating that the customer is not worth the cost of human labor. As a result, the shift of the Uncanny Valley forces brands into a radical bifurcation: either they accept the risk of rejection by falling into the abyss of the synthetic (where efficiency destroys empathy), or they embrace the deliberate inefficiency of the human and the imperfect as the only true sign of luxury and care.

The Failure of the “Easy Synthetic”: human saving<

Large companies such as Coca-Cola or McDonald’s, tempted by the efficiency of generative AI, have released campaigns (e.g. AI-generated Christmas commercials) that have been met with coldness or open hostility. The public perceived the “saving” of humanity as a lack of respect, identifying the content as worthless: time stolen from men. This saving of humanity does not seem to affect only the consumer market: even brands of the caliber of Deloitte have entered the controversy having been caught in fragrant for having sold the Albanian government a $290K AI slop

The Reaction to the “Synthetic”: Restoring Culture<

To understand the true nature of this transition, we must recognize today that we view advertising as an annoying invasion, a net cost of attention that we make in spite of ourselves.

The television series Maniac presents a dystopian reality in which it is possible to earn credits by passively listening to advertisements through an “ad-buddy”. This is the brutal representation of the social cost of marketing: an absorption of surplus, an anti-productive product, a thermodynamic loss of human culture.

In this scenario, the winning brands are not those that scream the loudest, but those that manage to become thermodynamically neutral systems in relation to cultural production. That is, they must reintegrate into the system the energy they have absorbed in excess from the profit of their products, returning it in the form of culturally relevant and free human labor (accessible to all). The “human” investment is therefore not a simple artisan whim, but the only way to balance the energy equation. Real cultural value is created and given back to compensate for the intrusion.

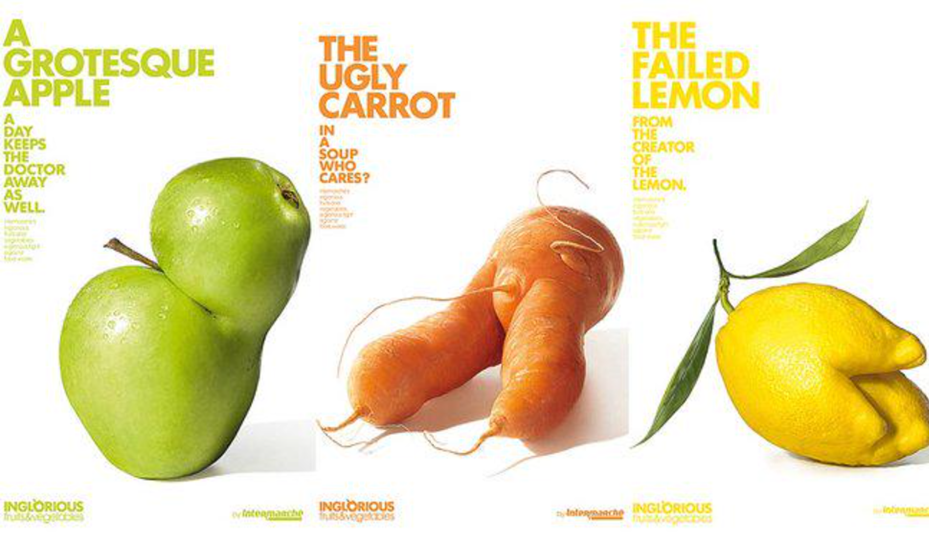

Among the most beautiful initiatives of 2025 are:

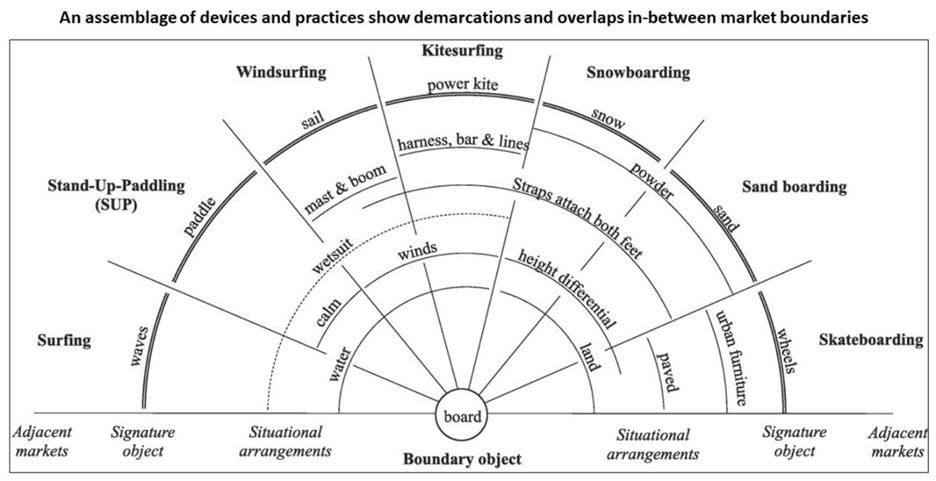

- Burger King Italia & Dungeons & Dragons: The release of a game manual illustrated by real artists, with an “indie” style even for the TTRPG genre: this choice is not accidental. Styles that were unpopular until recently are currently difficult to reproduce by LGM in “zero shot” tasks because they are out of distribution compared to average AI datasets.

- OpenAI and Analog: Paradoxically, the same company that is leading the AI revolution promotes itself with commercials shot on 30mm film, using analog grain to suggest that their product (Sora) has not been used.

- Intermarché (2025): The Pixar-style Christmas commercial Le Mal Aimé (Unloved), with a very high level of 3D animation and a complex emotional narrative, signals that massive investment in human talent is the only way to emerge from the background noise generated by machines.

5. Marketing as Problem Solving<

If in the previous chapter we analyzed the post-cognitive consequences (the moral and aesthetic reactions to the “paradox of efficiency”), here we must investigate the pre-cognitive mechanism that activates these judgments. What does our brain use, in fractions of a second, to distinguish a human product from a synthetic one? The answer does not lie in a qualitative dichotomy (Beautiful vs Ugly), but in a gradient of resistance: we recognize the human because it offers us the instant opportunity to transform ourselves from passive spectators to problem solvers. On the contrary, we perceive as “advertising”, “transactional” or “synthetic” everything from which this cognitive friction has been subtracted.

In the following sections we will elaborate further on this concept and provide practical guidance for marketeers.

Consumers as Problem Solvers<

- Classic Marketing: Message and Medium coincided perfectly: “x is y because z: you need y so buy x”. The communication is direct, unambiguous, aimed at sales and based on the mythology of the “low attention span” (the so-called myth of the goldfish according to which in 2015 the animal would have surpassed us in the span of attention by 1.2 seconds). An approach that culpably ignores the factual reality demonstrated by Steven Johnson’s Sleeper Curve: today we consume extremely more complex mediums than in the past. If we compare an old episodic TV series (e.g. Starsky & Hutch) with a modern narrative (e.g. Game of Thrones) or the evolution from the reactive video game (Pong) to the management/strategy one (Elden Ring), we notice an exponential increase in the variables that the brain has to manage simultaneously.

- Marketing As Problem Solving: The relationship between Medium and Message becomes a puzzle to be decoded, activating what Jason Mittell calls Forensic Fandom: a way of fruition where the user does not look passively, but acts as a forensic detective, analyzing frames, hidden details and implicit connections (as happens in the fandoms of Lost, Severance or Elden Ring).

- “Didacticism” is deliberately avoided, and in particular the narrative sin known as “As You Already Know Bob” (AYAK). AYAK is that lazy writing technique in which the characters exchange information that they both already possess (“As you know, Bob, we career moms always have little time for ourselves…”) for the sole purpose of feeding the viewer. Removing this “explanation” means stopping treating the consumer as a passive user.

- The result is an intellectual engagement: when the content is dense and culturally relevant, the attention span does not decrease, on the contrary: it is activated in “cognitive gym” mode.

- We can even overturn the narrative on the famous “three seconds” of attention: they are not proof of a cognitive deficit, but the confirmation of the Sleeper Curve. It is simply the time that a brain, now trained to process high narrative complexities, takes to “solve” the pattern of a trivial AYAK content, predict its ending and discard it as irrelevant.

A practical example of High-Context Marketing<

The Intermarché commercial, which tells of a wolf converted to vegetarianism for the love of conviviality, closes with the claim: “We all have a reason to eat better”. By choosing the register of the Aesopian fable, the brand avoids commercial didacticism (“at Intermarché you eat better”) in favor of an open morality. “Eating better” thus becomes a polysemic concept: health, inclusion, care or simply being together. This ambiguity is intentional: it signals that the brand does not want to impose a convenient truth, but to stimulate personal reflection. While AI tends to explain the obvious, human art works in sublimination, speaking simultaneously to the vegetarian, the health-conscious and the foodie, leaving each to complete the meaning.

High-Context Culture: Why the “Sign Shear” Works<

This mechanism finds a solid scientific basis in Edward T. Hall’s cultural anthropology, in particular in the distinction between High-Context and Low-Context cultures.

Artificial Intelligence intrinsically operates in a Low-Context regime: everything must be explicit, codified, said. There is no subtext because there is no common “experience” between machine and man.

On the contrary, emotionally relevant human communication is High-Context: it is based on a sort of “sign shear”, i.e. on the voluntary suppression of obvious information. The message is effective precisely because it is incomplete: much of the meaning does not lie in the words or images conveyed, but in the shared cultural context that the public already possesses. This omission is not an act of exclusion (as class theories on “cultural capital” would suggest), but an act of trust in collective intelligence: treating the public as a refined problem solver, capable of completing the pattern, creates a bond of complicity that the didactic machine cannot replicate.

Conclusions<

In conclusion, to navigate this dynamic new Uncanny Valley, marketing must ask itself a fundamental question that serves as a litmus test for cultural relevance:

“If we weren’t interested in the product itself, would we watch this content out of pure interest?”

If the answer is yes, it means that the brand has created something that transcends the commercial offer and has invested in human value, the only currency that maintains its purchasing power while AI devalues technical perfection.